Baseball Hall Of Fame Gambling

There have been many dramatic on-and-off-field moments in over 130 years of Major League Baseball:

Gambling scandals[edit]

Baseball had frequent problems with gamblers influencing the game, until the 1920s when the Black Sox Scandal and the resultant merciless crackdown largely put an end to it. The scandal involved eight players and all were suspended for life. They were not guilty of the scandal but were suspended for life for being around the shady characters.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/63801763/HALL_OF_FAME_BASEBALL_47850365_999x702.0.jpg)

On February 4, 1991, Rose's ban from baseball was extended to the Baseball Hall of Fame, when the twelve members of the board of directors of the Hall voted unanimously to bar Rose from the ballot. However, Major League Baseball allowed Rose to be a part of the All-Century Team celebration in 1999 since he was named one of the team's outfielders. Among the new additions to the BBWAA ballot, the highest career Wins Above Replacement figures, as calculated by Baseball Reference, belong to starting pitchers Buehrle (59.1) and Hudson (57.9) and outfielder Hunter (50.7). To put that in perspective, the average bWAR of Hall of Fame position players and pitchers is 69. The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York attracts more than 250,000 fans every year. (Image: YouTube/mrcheezypop) The board of directors voted unanimously to cancel 2020 Hall of Fame Induction Weekend in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

1877 Louisville Grays scandal[edit]

After a losing streak towards the end of the season cost the Louisville Grays the pennant, members of the team were discovered to have thrown games for money. Four players, including star pitcher Jim Devlin, were banned from professional baseball for life.

1908 bribery attempt[edit]

Two years after Rose accepted an indefinite ban from baseball in 1989 for gambling on games, the Hall of Fame said it would not place any player on the ballot who was on the ineligible list. Once again, Pete Rose is asking to be reinstated to Major League Baseball. Taking a page from Donald Trump, the legendary hitter (and gambler) admits no fault while harkening back to the sport’s.

On the eve of the 'playoff' or 'makeup' game between the Chicago Cubs and the New York Giants that would decide the National League championship, an umpire refused an attempted bribe intended to help the Giants win. The Giants lost to the Cubs, and the matter was kept fairly quiet. It came out the following spring, but the results of the official inquiry were kept secret. However, the Giants' team physician for 1908 was reportedly the culprit and was banned for life.

Recent research has suggested that the team physician was allowed to be the 'scapegoat'; some baseball historians now suspect that the Giants' manager, John McGraw, was behind the physician's bribe attempt, or that it may in fact have been McGraw himself who approached the umpire. If true, and had it become known, it could have been disastrous, as McGraw was such a prominent figure in the game.

1914 World Series upset[edit]

The four-game sweep of the Philadelphia Athletics by the Boston Braves in the 1914 World Series was stunning. Students of that Series suspect that the Athletics were angry at their notoriously miserly owner, Connie Mack, and that the A's players did not give the Series their best effort. Although such an allegation was never proven, Mack apparently thought that it was at least a strong possibility, and he soon traded or sold all of the stars away from that 1914 team. The A's team was decimated, and within two years they limped to the worst single-season win-loss percentage in modern baseball history (36-117, .235); it would be over a decade before they recovered.

1917–1918 suspicions[edit]

The manner in which the New York Giants lost to the Chicago White Sox in the 1917 World Series raised some suspicions. A key play in the final game involved Heinie Zimmerman chasing Eddie Collins across an unguarded home plate. Immediately afterward, Zimmerman (who had also hit only .120 during the Series) denied throwing the game or the Series. Within two years, Zimmerman and his corrupt teammate Hal Chase would be suspended for life, not so much due to any one incident but to a series of questionable actions and associations. The fact that the question of throwing the Series was even raised suggests the level of public consciousness of gamblers' potential influence on the game.

Then, just a year ahead of the infamous Black Sox scandal, there were rumors of World Series fixing by members of the Chicago Cubs. The Cubs lost the 1918 Series in a sparsely-attended affair that also nearly resulted in a players' strike demanding more than the normal gate receipts. With World War I dominating the news (as well as having shortened the regular baseball season and having caused attendance to shrink) the unsubstantiated rumors were allowed to dissipate.

1919 conspiracy[edit]

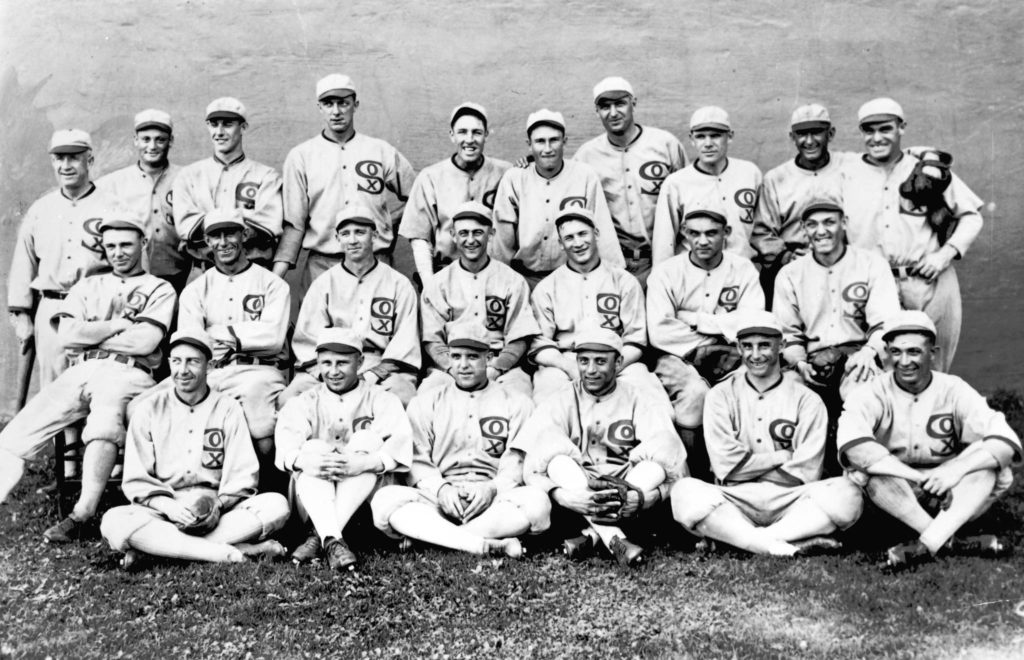

The 1919 World Series resulted in the most famous scandal in baseball history, often referred to as the Black Sox Scandal. Eight players from the Chicago White Sox (nicknamed the Black Sox) were accused of throwing the series against the Cincinnati Reds.

Details of the scandal remain controversial, and the extent to which each player was said to be involved varied. It was, however, front-page news across the country when the story was uncovered late in the 1920 season, and despite being acquitted of criminal charges (throwing baseball games was technically not a crime), the eight players were banned from organized baseball (i.e. the leagues subject to the National Agreement) for life.

Although betting had been an ongoing problem in baseball since the 1870s, it reached a head in this scandal, resulting in radical changes in the game's organization. It resulted in the appointment of a Commissioner of Baseball (Kenesaw Mountain Landis) who took firm steps to try to rid the game of gambling influence permanently.

One important step was the lifetime ban against the Black Sox Scandal participants. The 'eight men out' were the great 'natural hitter' 'Shoeless' Joe Jackson; pitchers Eddie Cicotte and 'Lefty' Williams; infielders 'Buck' Weaver, 'Chick' Gandil, Fred McMullin, and 'Swede' Risberg; and outfielder 'Happy' Felsch. Jackson, who was suspended during the peak of his career with a .356 lifetime batting average (all-time third), is still regarded as one of the greatest players not in the Hall of Fame.

1919 aftermath[edit]

Baseball Hall Of Fame Gambling Game

After the 1919 scandal and some further game-fixing incidents in 1920 had been resolved, and with Landis having taken over, the gambling problem apparently went away, for the most part, for decades. Commissioners have taken an almost fanatical interest in the subject, suspending well-known individuals for lengthy times just for having been seen with gamblers; Leo Durocher, manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, was suspended by Commissioner Happy Chandler for the 1947 season for just that reason.

After their retirement, Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays served for a while as greeters at legal Atlantic City gambling casinos. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn issued a ban against them. New Jersey state gaming regulators harshly criticized Kuhn's decision, while newspaper articles of the time pointed out that Mantle and Mays played before there were large player salaries. Their bans were lifted during Commissioner Peter Ueberroth's term.

1980s Pete Rose betting scandal[edit]

Baseball Hall Of Fame Gambling Losses

In March 1989, Pete Rose, baseball's all-time hits leader and manager of the Cincinnati Reds since 1984, was reported by Sports Illustrated as betting on Major League games, including Reds games, while he was the manager.

Rose had been questioned about his gambling activities in February 1989 by outgoing commissionerPeter Ueberroth and his successor, National LeaguepresidentA. Bartlett Giamatti. Three days later, lawyer John M. Dowd was retained to investigate the charges against Rose. During the investigation, Giamatti took office as the commissioner of baseball.

The Dowd Report asserted that Pete Rose bet on 52 Reds games in 1987, at a minimum of $10,000 a day.

Rose, facing a very harsh punishment, along with his attorney and agent, Reuven Katz, decided to seek a compromise with Major League Baseball. On August 24, 1989, Rose agreed to a voluntary lifetime ban from baseball. The agreement had three key provisions:

- Major League Baseball would make no finding of fact regarding gambling allegations and cease their investigation;

- Rose was neither admitting or denying the charges; and

- Rose could apply for reinstatement after one year.

Despite the 'no finding of fact' provision, Giamatti immediately stated publicly that he felt that Rose bet on baseball games. Eight days later, September 1, Giamatti suffered a fatal heart attack. The consensus among baseball experts is that Giamatti's post-agreement statement, his sudden and untimely death, and appointment of new commissioner, Fay Vincent, a close friend and great admirer of Giamatti, doomed Pete Rose's hopes of reinstatement.[citation needed]

Bud Selig, the former owner of the Milwaukee Brewers, succeeded Vincent in 1992. Rose has applied for reinstatement twice: in September 1997 and March 2003. In both instances, commissioner Selig chose not to act, thereby keeping the ban intact. Upon Selig's retirement from the Commissioner's Office, Rose applied for reinstatement in March 2015, but Selig's successor Rob Manfred denied the request in December of that year.

On February 4, 1991, Rose's ban from baseball was extended to the Baseball Hall of Fame, when the twelve members of the board of directors of the Hall voted unanimously to bar Rose from the ballot. However, Major League Baseball allowed Rose to be a part of the All-Century Team celebration in 1999 since he was named one of the team's outfielders.

In 2004, after years of speculation and denial, Rose admitted in his book My Prison Without Bars that the accusations that he had bet on Reds games were true and that he had admitted it to Selig personally some time before. He stated that he always bet on the Reds, never against them.[1]

1980s collusion[edit]

Repeatedly in the 1980s, MLB owners colluded to keep player salaries down. Over multiple instances the owners were found to have stolen nearly $400 million from the players. When the Major League Baseball players struck in 1994, the owners were found to have committed unfair labor practices in attempting to keep player salaries down again.[citation needed]

Substance abuse[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Doping in sport |

|---|

|

|

|

Baseball has had its share of problems with substance abuse from the inception. Prior to the 1970s, there were countless individual problems with alcohol abuse, but as alcohol was a legal substance during most of that time (except for the Prohibition era), alcohol was typically seen as a character weakness on the part of individuals. Public awareness of illegal drugs accelerated during the 1970s, and by the 1980s a number of players had become caught up.

1985 cocaine scandal[edit]

Pittsburgh Pirates players Dave Parker, Dale Berra, Rod Scurry, Lee Mazzilli, Lee Lacy, and John Milner, as well as non-Pirates Willie Mays Aikens, Vida Blue, Enos Cabell, Keith Hernandez, Jeffrey Leonard, Tim Raines, and Lonnie Smith, were summoned to appear before a Pittsburghgrand jury. Their testimony led to the Pittsburgh Drug Trials, which made national headlines in September 1985.

The spotlight on the 'Pittsburgh problem' by the national media led to the more widespread awareness of use of other drugs such as amphetamines ('greenies' in baseball vernacular) and marijuana[citation needed] in the game. Both have a long history in baseball; Milner (who had retired two years earlier due to recurring hamstring injuries), in fact, spoke of Willie Mays and Willie Stargell, both iconic figures and Baseball Hall of Famers, giving him 'greenies'.

Testimony revealed that drug dealers frequented the Pirates' clubhouse. Stories such as Rod Scurry leaving a game in the late innings to look for cocaine and John Milner buying two grams of cocaine for $200 in the bathroom stalls at Three Rivers Stadium during a 1980 game against the Houston Astros shocked the grand jurors. Even Kevin Koch, who played the Pirates' mascot, was implicated for buying cocaine and introducing players to a drug dealer. Ultimately, seven drug dealers pleaded guilty on various charges.

On February 28, 1986, Baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth suspended a number of players for varying lengths of time. A primary condition of reinstatement was public service. It would have also included urine tests, but the players union was able to successfully halt its implementation. To this day, drug testing, particularly of this sort, is a polarizing issue.

Rod Scurry died at age 36 on November 5, 1992 in a Reno, Nevadaintensive care unit of a heart attack after a cocaine-fueled incident with police officers led to his hospitalization.

2005–2006 steroids investigations[edit]

The steroids rumors and facts resulted in several de facto bans from the game by players who were either certifiable or suspected users of steroids, and significant doubt has been cast about the quality of various baseball records set since at least the early 1990s. Some people base their opinion on Jose Canseco's tell-all book Juiced: Wild Times, Rampant 'Roids, Smash Hits & How Baseball Got Big.

2013 Biogenesis scandal[edit]

In 2013, twenty Major League Baseball (MLB) players were accused of using HGH after obtaining it from the clinic Biogenesis of America. Milwaukee Brewers star Ryan Braun, who had a drug-related suspension overturned in 2011, made a deal with MLB and accepted a 65-game ban. Two weeks later, New York Yankees star Alex Rodriguez was suspended through the 2014 season (211 games), and 12 other players were suspended for 50 games. It was the most players ever suspended at one time by MLB.

Sign stealing scandals[edit]

In 2019, Mike Fiers of the Oakland Athletics spoke to Ken Rosenthal and Evan Drelich of The Athletic where he revealed the Astros had been electronically stealing signs since at least the 2017 season. After an investigation by MLB, Astros manager AJ Hinch and general manager Jeff Luhnow were each suspended for one year from MLB. In addition, the Astros were fined $5 million and lost their first- and second-round draft picks for the 2020 and 2021 MLB drafts. After the news broke, Astros owner Jim Crane fired both Hinch and Lunhow. Hinch admitted to knowing about the scheme and discouraging it, but not reporting or stopping it. Both Carlos Beltrán and Alex Cora were also implicated in the report by MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred. The Boston Red Sox, managed by Cora beginning in the 2018 season, were also accused in a story on The Athletic of having their own sign stealing scheme.

On January 14, 2020, Cora and the Red Sox agreed to 'mutually part ways'. In a statement after the news Cora said, 'I do not want to be a distraction'. The report on the Red Sox scheme was not released before the decision. Two days later, Beltrán and the New York Mets came to a similar parting of the ways; the Mets had hired him as the team's new manager less than three months earlier.

On April 22, 2020, MLB suspended Red Sox video replay system operator J.T. Watkins without pay through the 2020 postseason and stripped the team of its second-round draft pick this year after completing an investigation into allegations that Boston stole signs during the 2018 season. Alex Cora was also suspended through the 2020 postseason, but only for his conduct as Houston's bench coach [2]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^Pete Rose#Coming clean

- ^https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/29083660/mlb-suspends-red-sox-replay-operator-1-year-docks-draft-pick-punishment-sign-stealing-scandal

- Sources

- Eight Men Out, by Eliot Asinof

- Rose, Pete; Hill, Rick (2004). My Prison Without Bars. Rodale Press. ISBN1-57954-927-6.

Pete Rose was recently asked who the greatest player not in the Baseball Hall of Fame was. Rose, who knows a thing or two about the subject, named “Shoeless” Joe Jackson. That got us to thinking. Who are the best MLB players not in the Hall of Fame.

To sort this out, we must establish two quick guidelines. First, we’re dealing exclusively with MLB players. Plenty of great Negro League players were deprived of the chance. Unfortunately, finding complete Negro League stats is nearly impossible. Fortunately, the Hall of Fame has done a decent job honoring them. Second, players who played in 2014 and on haven’t even been on a ballot. Since not everyone can be a first ballot Hall of Famer, we’ll exclude players who have played since 2010. Still, that leaves plenty of good options.

A good chunk of our players were in 2007’s Mitchell Report. Still, alleged PED use isn’t the only thing keeping players out. Rose and Jackson are both out for other reasons. A man who pitched against many of the best players listed in the Mitchell Report is also not in, despite having brilliant numbers. In one case, a potential Hall of Fame career was cut tragically short.

The Baseball Hall of Fame has an abundance of worthy candidates yet to be enshrined. These are the best players not in Cooperstown.

10. Thurman Munson

Munson passed away in 1979 when a plane that he was piloting crashed. Munson was a seven-time All-Star, won three Gold Gloves, the 1970 AL Rookie of the Year, the 1976 AL MVP, and caught for two World Series champions. He was also the captain of the New York Yankees since Lou Gehrig. That’s quite a distinction when we think of the great Yankees who played between Gehrig and Munson. While he hadn’t quite built a Hall of Fame resume at that the time of his death, Munson was well on his way.

9. Sammy Sosa

Sosa is one of only nine men in MLB history to have 600 career home runs. He’s also the only man to top 60 home runs in a season on three separate occasions. Sosa and Mark McGwire (more on him later) also renewed interest in baseball in 1998 when so many fans were still turned off from the 1994-95 strike. As huge as his impact was, Sosa was in the Mitchell Report. None of those players are in Cooperstown. Unfortunately for Sosa’s massive impact and gaudy stats just couldn’t overcome the Mitchell Report stain.

8. Gary Sheffield

Sheffield could be productive in any lineup hitting at any ballpark. After all, he played for eight teams. He was a career .292/.393/.514 hitter and hit 509 home runs. Sheffield just hit everywhere he played. Much like Sosa, Sheffield’s place in the Mitchell Report has done a lot to keep him out of the Hall of Fame. Many of great hitters are in the Hall of Fame. More than just a select few were nowhere near as productive or as feared as Sheffield in their careers.

7. Rafael Palmeiro

Palmeiro finished his career with 3,020 hits and 569 home runs. For reference, only four other players (Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Alex Rodriguez, and Eddie Murray) have notched both 3,000 hits and 500 home runs. Unfortunately for Palmeiro he’s not just a Mitchell Report guy. He’s one of its cover boys. Palmeiro was one of the first players (and the first star) to test positive for PEDs under the new policy in 2005. That flew in the face of what he had defiantly told Congress just before the season. The end result was a sad conclusion to a fantastic career.

6. Curt Schilling

Schilling is often labeled a big-game pitcher. While there are worse labels to have, Schilling was much more. In his career Schilling posted a 3.46 ERA, a 1.137 WHIP, and 3,116 strikeouts with an 8.6 K/9 rate. That compares very well to Tom Glavine (3.54 ERA, 1.314 WHIP, 2,607 strikeouts, 5.3 K/9) and stacks up reasonably well to Greg Maddux (3.16 ERA, 1.143 WHIP, 3,371 strikeouts, 6.1 K/9). Schilling has argued that his outspoken political views have kept him out. Maybe you agree. Maybe you don’t. But Glavine and Maddux were first ballot Hall of Famers, receiving 91.9% and 97.2% of the vote, respectively. Schilling is still waiting for the call.

5. Mark McGwire

Always one of baseball’s most feared and powerful hitters, McGwire had issues staying healthy through much of his career. In 1998, that changed. He hit a then record 70 home runs and along with Sosa filled ballparks around MLB through the entire summer. While his career .263 average is not too impressive, the .394 OBP and .588 slugging percentage more than make up for it, especially when we add his 584 career homers. Like many others, McGwire’s alleged PED use has kept him out of Cooperstown. Whether that’s fair can be debated. McGwire’s impact on baseball at a time when it was needed was massive. That’s not up for debate.

4. Joe Jackson

Jackson was one of eight members of the 1919 Chicago White Sox to receive a lifetime ban for conspiring to throw that year’s World Series. While he’s not the only one with Hall of Fame caliber credentials, Jackson was the best player of that bunch. His .356 career batting average remains the third-highest in history. His career predated the home run boom that came with Babe Ruth. Still a career .517 slugging percentage tells us that Jackson was not simply a slap hitter. While his plight was overly romanticized in “Field of Dreams,” Shoeless Joe was undeniably one of the greatest players ever.

3. Roger Clemens

Baseball Hall Of Fame Gambling Hall Of Fame

Like so many other superstars not in Cooperstown, Clemens is in the Mitchell Report. Unlike most (though not quite all) of them, the general consensus is that he was using PEDs late in his career. In other words, the PEDs might have helped him play at a high level late. Still, Clemens built his Hall of Fame credentials before any wrongdoing took place. All told, Clemens retired with a 3.12 ERA, a 1.17 WHIP, 4,672 strikeouts, and a record seven Cy Young Awards, which he won with four different teams. That’s easily Hall of Fame worthy.

NFL Reckless Speculation Podcast – LISTEN NOW

Subscribe on: Apple / Stitcher / Google / Spotify / RSS

Baseball Hall Of Fame Gambling Odds

2. Pete Rose

Rose’s 4,256 hits are an MLB record. If we revisit this in 100 years, don’t expect that to change. Rose is a three-time World Series champ, made 17-time All-Star teams, claimed two Gold Gloves, and was the NL Rookie of the Year in 1963 and the MVP in 1975. For betting on baseball, Rose was banished in 1989. Like Jackson and the Black Sox, that ban includes the Hall of Fame. It’s hard to feel much sympathy for him. The no gambling rule didn’t sneak up on him. Still, looking solely at his playing credentials , Rose is clearly a Hall of Famer.

1. Barry Bonds

When 1998 ended, Bonds was a .290/.411/.556 career hitter, had 411 career homers, 445 steals, was an eight-time All-Star, won eight Gold Glove Awards and was a three-time MVP. At that point, the PED use began, at least according to the Mitchell Report. Over the next decade, Bonds would win four more MVPs (nobody else has more than three), got to 500-500 (he’s still the only 400-400 player), and became MLB’s home run king (both career and single-season). Whether he should be kept out of the Hall of Fame is debatable. But both before and after the alleged PED use, nobody out of Cooperstown is as good as Bonds. That’s clear.